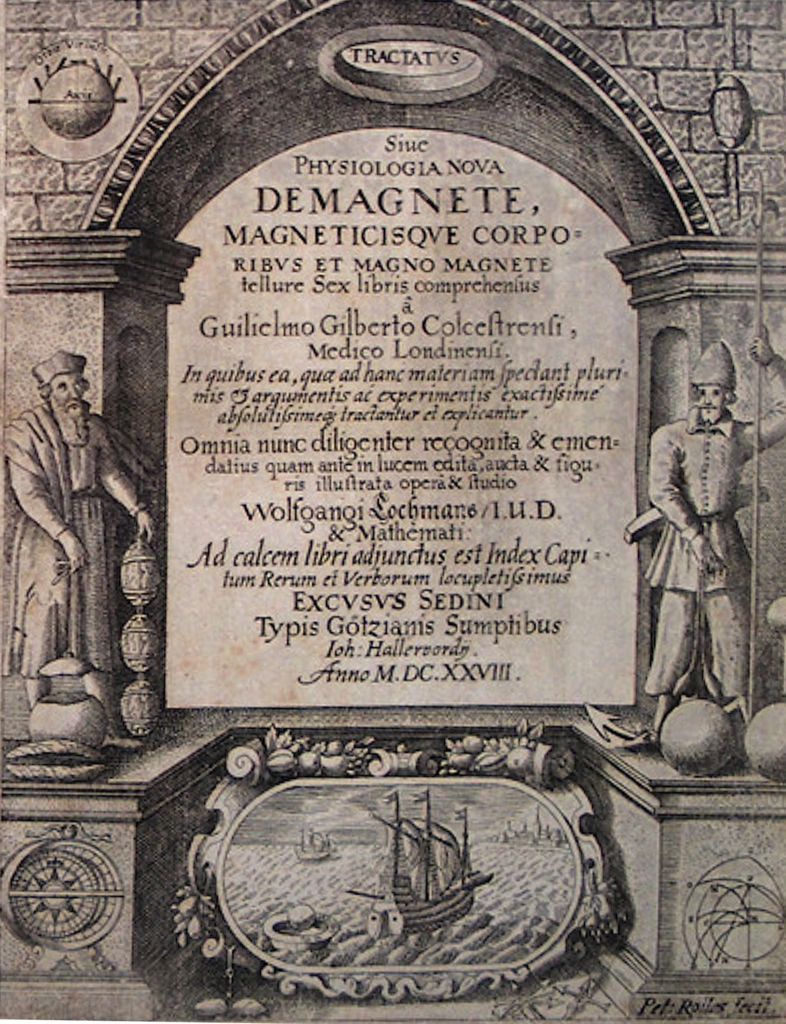

In 1600 the English physician and natural philosopher William Gilbert published “De Magnete” (On the Magnet, Magnetic Bodies, and on the Great Magnet of the Earth), a pioneering six volume treatise on magnetism and electricity that was the culmination of his eighteen years of study and experimentation. This seminal work of Gilbert laid the foundations for the scientific study of magnetism and was so thorough and complete that hardly anything new of value was added to the field until the discovery of electromagnetism by Michael Faraday in the 1820s.

William Gilbert and his Experiments on Magnetism and Electricity

William Gilbert was born on May 24, 1544 in Essex, entered the medical profession and became a successful and wealthy physician, a career that culminated in becoming Queen Elizabeth I personal physician. As was the case with most natural philosophers of his time, his wealth provided him the leisure time to work as an amateur scientist, and while he was originally interested in chemistry, he eventually settled on studying magnetism, a phenomenon that up to that time had essentially been ignored by science. During his time working in the medical profession, Gilbert simultaneously conducted his research on magnetism and electricity.

Gilbert made several claims about magnetism in his book. He commented on magnetism in nature, experimenting with different materials, but in particular he carried out experiments using a lodestone. The properties of the lodestone were known for centuries, but hardly anything was known about how or why it worked the way it worked. Gilbert identified the lodestone as a naturally occurring magnet that was capable of attracting iron and other materials. He noted that the attraction was not only directional, but that it also varied over distances. As the distance increased the magnetic force became weaker. He showed the lodestone could induce magnetism in other materials. For example, when iron was brought into contact with it, the iron acquired its magnetic properties.

Gilbert was the first person to distinguish between north and south poles, while coining their names. Through his experiments he demonstrated that like poles repel each other, while opposite poles attract.

One of Gilberts most significant claims was that the Earth works as a giant magnet, with its magnetic field affecting the needle of compasses. He conducted experiments to show how a compass needle aligns with the Earth’s magnetic field. He also identified the Earth as having magnetic poles. The experiments he conducted showed compass needle points towards a magnetic north, rather than a geographic north pole. In his book, he described experiments where he suspended a magnetized needle freely and observed that it consistently pointed towards the magnetic north, independent of its original orientation. He described in detail the behavior of the compass in various locations. These observations became crucial for navigation.

Impact of De Magnete

The late Renaissance was a period of increasing scientific curiosity, but it was still heavily entranced in Aristotelian philosophy. When considering the impact of De Magnete, the book had an impact in what he discovered for sure, but what was truly revolutionary was how he made his discoveries. Not only did it expand our knowledge about magnetism, but it aided in changing the way people did science. Gilbert established the scientific method as his means to discovery and it had a direct impact on the future generation of scientific minds, especially on Galileo Galilei and later on Isaac Newton.

However, the immediate impact of De Magnete was probably most felt on navigators and explorers. The compass had been around prior to the book’s publication but there were many misunderstandings and superstitions associated with it. Gilbert laid the foundations for geomagmatism, allowing for better understanding and design of the compass. Finally, navigators could begin to understand why the compass worked, leading to better techniques associated with its usage and less fear and guesswork of a “cursed” instrument.

Lastly, Gilbert’s ideas provided a catalyst for the further study of magnetism. Future scientists such as Johannes Kepler explored magnetic forces in cosmology while later researchers, such as Carl Friedrich Gauss, formalized the mathematics of geomagnetism. He also distinguished the difference between static electricity and magnetism, inspiring the work of Michael Faraday, Hans Christian Orsted, culminating in their unification as electromagnetism by James Clerk Maxwell.

William Gilbert’s work was clearly ahead of his time, but it planted the seeds of which the modern scientific method grew out of. His work is a testament to the power of curiosity and experimentation – a legacy as magnetic as the forces he sought to understand.

Continue reading more about the exciting history of science!