After thirty years of research, William Harvey’s landmark book On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals established once and for all that blood flow was entirely circular and that the heart was a pump. The discovery of blood circulation was transitory for a few important reasons. It established the principle of experimentation in medicine. It helped to create the new field of physiology. Lastly, it marked the beginning of the true understanding of our circulatory system with additional details to emerge later on.

A Brief History of the Cardiovascular System up to Harvey

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The ancient Greeks, those pioneers of scientific discoveries, once again lead the way in the fields of medicine and physiology in antiquity. It was understood by the Geeks that the peripheral parts of the body required nourishment. The mystery was how this was accomplished. The first detailed attempt at this explanation (that rejected divine causes) was put forth by Hippocrates of Cos and his pupils. It was grounded in humorism, a doctrine declaring that health was maintained by a balance in humors (bodily liquids). Disease was caused by an imbalance in these humors. Various Greek thinkers, including Praxagoras, Erasistratus, and Aristotle, identified the heart, veins, and arteries and theorized about their role in the blood system.

The next notable advancements came from Galen. Born during the second century AD at the height of the Roman Empire, he built on the systems he inherited from the Greeks while adding new information along the way. He carried out many experiments on animals, however none on humans. He was accumulated an array of facts and inherited ideas from which he attempted to deduce how the entire system worked. He differentiated between arteries and veins and proved that they both contain blood. This differed from Erasistratus’ view that arteries only contained air. He noted that the heart pulsated, that everything breathes, and made connections between the liver, heart, and lungs. While his system was complicated it was nowhere near as complicated as the human body’s system actually is. It can be summarized as the liver, veins, and the right side of the heart were to deliver nourishment to the peripheral parts of the body. Blood was thought to be manufactured in the liver, traveled to the peripheral parts of the body through the veins where the tissues take up its nourishment. The lungs, arteries, and the left side of the heart were to deliver fresh air and to cool the body.

The middle ages in Europe provided little advancement in knowledge. During this time the Catholic Church rose to power and suppressed any idea’s conflicting with Christian doctrine. Experimentation was discouraged and any new discoveries, such as Andreas Vesalius’s dissections or Realdo Colombo’s of pulmonary circuit, were made to fit in with Galen’s previously existing ideas, or ignored. This void of progress lasted about a thousand years, up to the time of the Renaissance.

William Harvey’s Contributions

The man who finally solved the riddle of the pathway of blood in the body was William Harvey. Born in 1578 during the Scientific Revolution, Harvey attended the University of Padua, the greatest medical school of its time. There he learned Galen’s physiology and throughout his life he still held on to some notions of ancient doctrine. However like many of the famous early scientists of his era he was not afraid to challenge it. He was very interested in academics and in his late 30s he decided to tackle the problem of how the heart works.

First, Harvey worked with animals to make his observations, sometimes cutting the chest of the animal open to watch what happens to the heart as the animal dies. Through his dissections, he was able to identify a thrusting motion which we now call systole, where the blood is moved out through the body. More specifically, he noticed that blood returns to the heart and fills up the atrium, the two chambers above the heart. When the atrium becomes full, the blood empties into the ventricles below, which then pump the blood out to the lungs and rest of the body. These studies become to topic of his lectures as the Lumleian Lecturer at the Royal College of Physician’s, and became the raw material for the first seven chapters of his later book On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals. Additionally, his experiments with animals showed that that blood flows away from the heart in arteries and towards the heart in veins.

It had also made little sense to Harvey that so much blood should be going out to nourish the body with so little of it returning. Was it really possible that the liver could really make so much blood? He decided to make some rough estimates of the volume of blood passing through the heart. First, he noted that a human heart could hold about two ounces of water. He multiplied that by an average number of beats per minute, and took that figure times sixty for each minute in an hour. This lead to a conservative estimation showing that about at least hundreds of pounds of blood must flow through the heart in an hour. Clearly there was no way the body could produce this amount of blood each day. By simple deduction this proved that blood flow must be circular. The question became how did the blood come back?

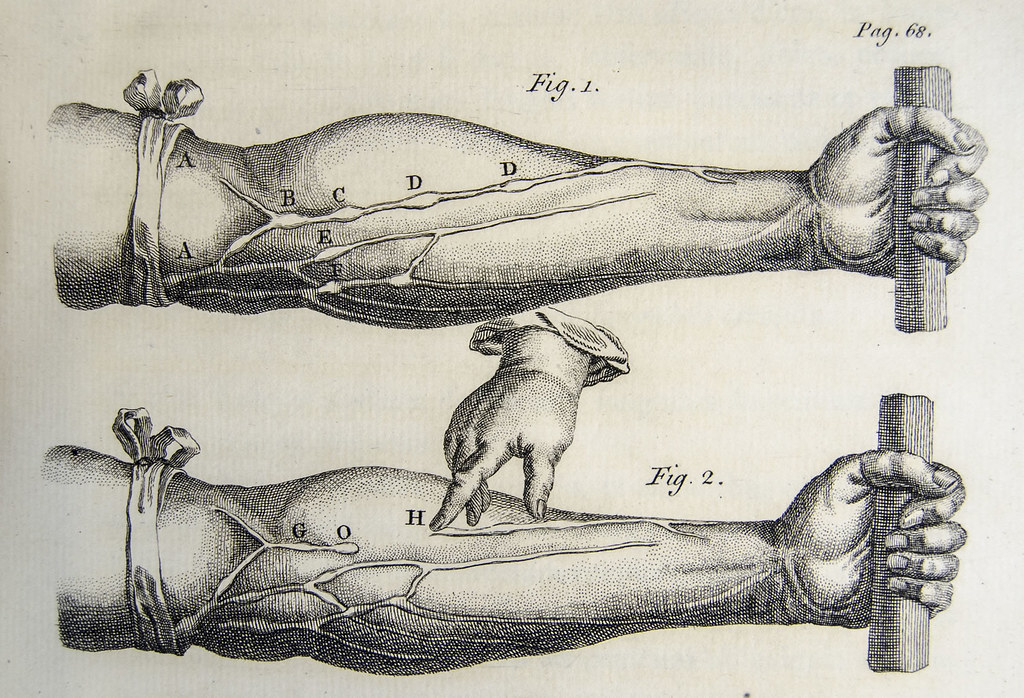

His teacher at the University of Padua was a man named Fabricius who discovered the values in the veins but could not explain their function. By compressing veins at various places of the body, Harvey showed that blood flows from the periphery to the center of the body and that blood flows in one direction. The valves keep the blood from reversing direction.

Although Harvey proved blood circulation, he work had little immediate effect. Blood letting continued for some time and the clinical value of understanding blood circulation seems of little importance. In the long run, it marked the end of the Galenic theory and marked an important turning point for modern medicine.

Continue reading more about the exciting history of science!