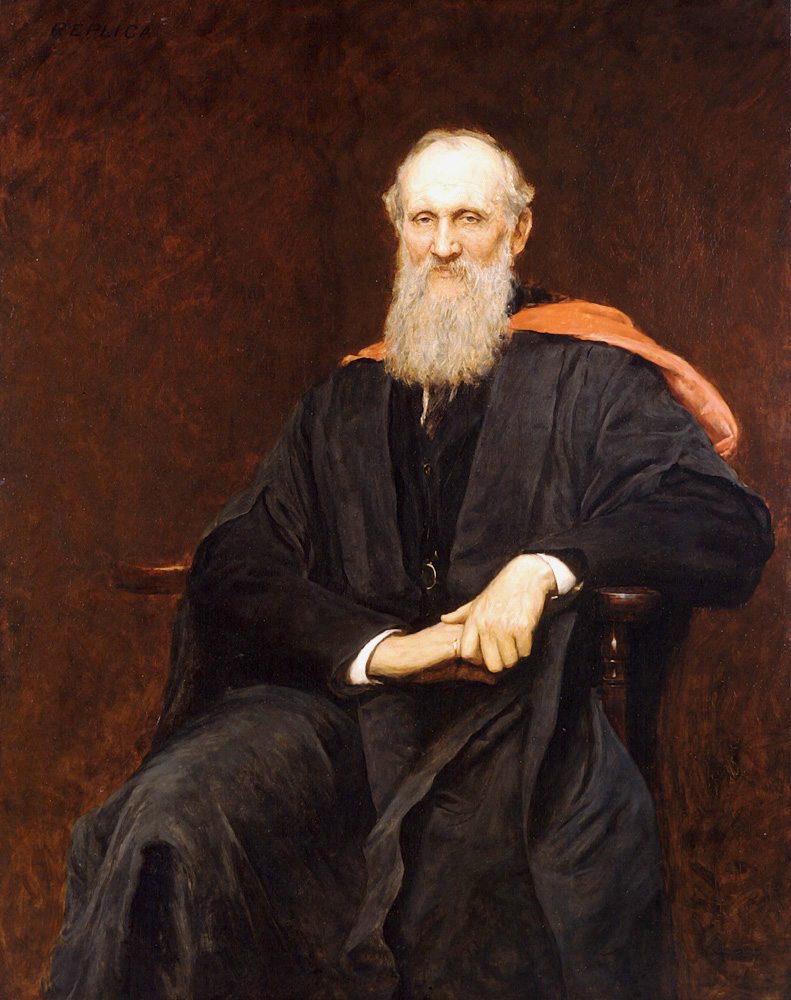

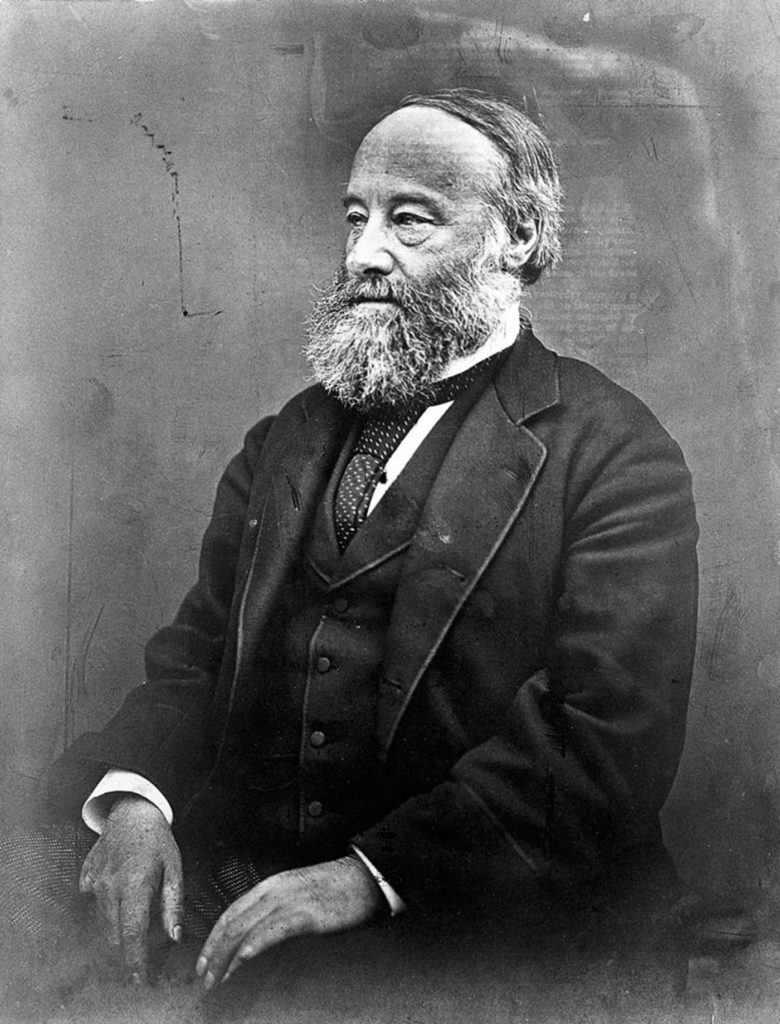

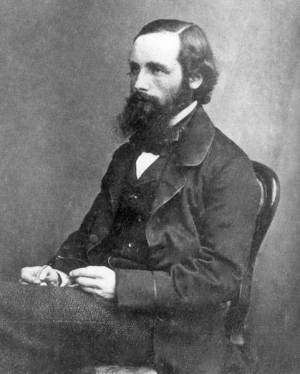

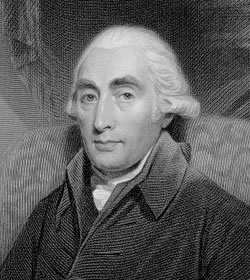

James Hutton (1726 – 1797) is widely considered the “Father of Modern Geology” as the originator of the theory of uniformitarianism – the idea that the physical features of the Earth have evolved slowly over time and the same natural processes are still at work today. He was a meticulous observer who noticed and extrapolated the effects that volcanoes, erosion and other slow moving processes would have on the planet.

Hutton was born in Scotland and attended the University of Edinburgh at age fourteen and completed courses at various universities throughout Europe. After his schooling Hutton worked on a farm that he had inherited. This work provided him with first-hand experience in observing the landscape while cultivating his interest in the features of the Earth’s surface.

His ideas on geology began to form in the 1760s, however he was never in a rush to publish his work. In fact it took him nearly 25 years before his Theory of the Earth was read to the Royal Society of Edinburgh. This work laid the foundations for modern geology and seeded the idea of uniformitarianism. Hutton inferred from his observations that the enormous pressure and heat of the inner Earth could provide the energy to fuse and chemically change sediments into new rocks. These rocks were eventually lifted out of the Earth through natural processes to form mountains. Over time erosion reduced the rocks to sediments which were buried layer under layer and returned to the inner Earth. This process is cyclical, and has occurred many times over. Hutton’s ideas were unpopular initially, in part because they were in contract with the teachings of the Christianity.

Over time his ideas were further developed and promoted by Charles Lyell, who in turn strongly influenced Charles Darwin’s Theory Evolution by Natural Selection. Hutton himself stated the basic principle of evolution by natural selection in 1794 which lacked the overwhelming evidence that Darwin had accumulated to prove it.