The Shackles of Superstition

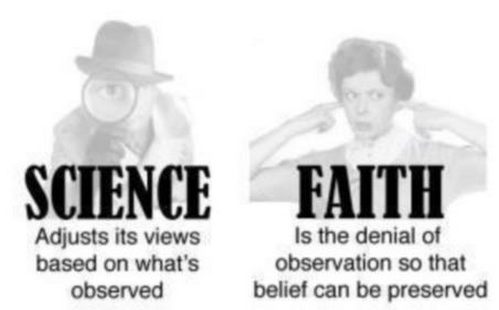

Science doesn’t hunt for miracles, it digs for the hard, stubborn truth of facts, making science the true force for progress in our world. For thousands of years, people lived scared, crushed by a world they couldn’t figure out, turning to gods, signs, and old stories to make sense of the mess. Plagues tore through towns like a punishment from above, blamed on sin or an angry deity, not the rats or dirty water we’d spot today. Storms ripped houses apart, their roars called the work of sky gods like Thor smashing his hammer or some heavenly fury, not the wind and heat we now track with our scientific instruments. The stars sparkled up in the sky, a giant puzzle, read like a fortune teller’s map, not the blazing balls of fire we know they are. Superstition was our first home, a cozy blanket of tales that felt good but did nothing. They provided no way to guess the next disaster, no cure for the sick, no chance to push back against nature’s chaos or the rules of priests who acted like they owned the truth.

This wasn’t just not knowing; it was a whole setup, a way of seeing the world built on fear and held up by power. In places like ancient Mesopotamia, priests cut open animals to guess what was coming, staring at guts like they held secrets. In medieval Europe, monks scribbled prayers to stop the Black Death, half the people died anyway, and all they got was more smoke from church candles. The Church, that huge machine of crosses and control, called the shots, its leaders trading comfort for loyalty. A comet lit up the sky in 1066, and they said it was God warning of war, not just a rock flying by. An earthquake smashed Lisbon in 1755, and preachers pointed at bad behavior, not the ground shifting under their feet. Answers were rare, twisted through holy books and old habits, while life stayed short, tough, and dim. Superstition didn’t just explain things, it kept folks down, hands folded, waiting for a rescue that never showed up.

The Fight Begins

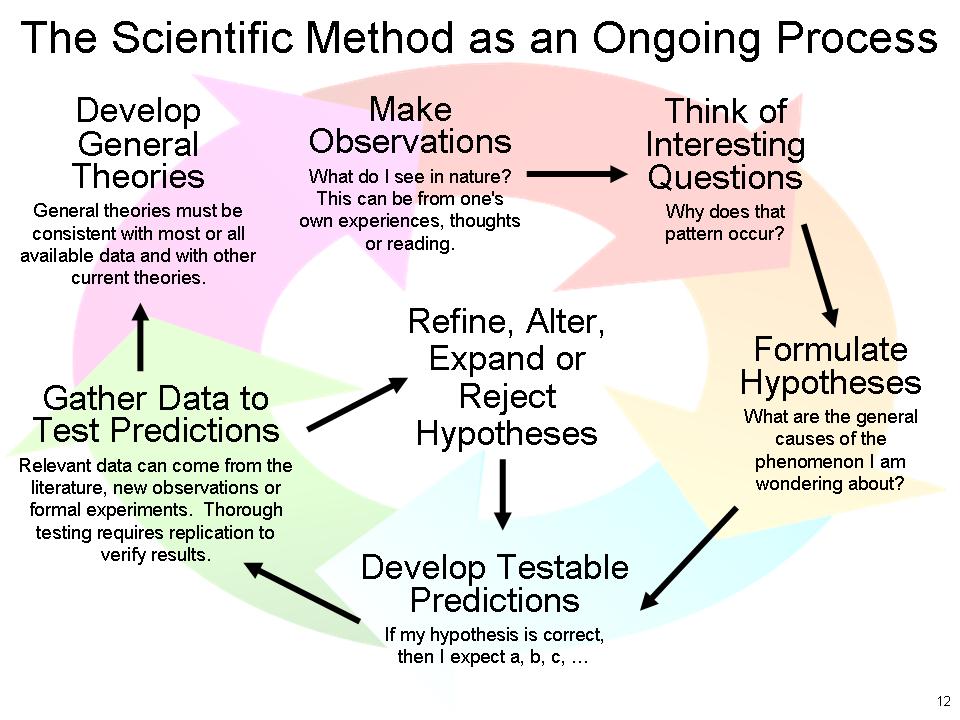

Then came a slow, tough shift: science as a force for progress began watching, testing, and daring to ask why to the established belief systems. Science didn’t burst onto the scene all at once, it scratched and clawed its way up, like a fighter in the dirt, breaking free from the old rules bit by bit. This wasn’t a quick happy ending; it was a long scrap, stretching over hundreds of years, usually against loud pushback from folks glued to the past. Picture Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543, a quiet church guy in a cold Polish tower, scratching numbers by candlelight, bold enough to say Earth wasn’t the center of everything, no matter what the Church growled. His star maps and sums didn’t just draw a new sky, they showed science as a force for progress when they chipped away at a holy wall that had stood forever. Or think of Louis Pasteur in 1865, squinting through a microscope in a messy lab, showing tiny germs, not God’s bad mood, killed people, tossing out old ideas of bad air and prayers.

Every win was a struggle, a shove against the stuck ways. William Harvey cut up bodies in 1628, seeing blood move through valves, not float on magic breezes, while Oxford doctors hugged their leeches and laughed. Edward Jenner, in 1796, poked a kid with cowpox, stopping smallpox with a farm girl’s trick, not a preacher’s words. Charles Darwin, sailing the Beagle in the 1830s, jotted down notes on birds and bones, building a story of life that went back millions of years, not a quick six-day job despite what the Bible claims. These weren’t battles fought with swords or speeches, but with proof: telescopes spotting planets, knives mapping the body, shots beating diseases, wires lighting the night. Little by little, science pulled us from shaky wonder into a light that was bright, even if it stung, a place where asking beat obeying, and facts buried fairy tales.

The pushback was loud, and no surprise, the Church had power to protect. Galileo Galilei stared down the Church’s court in 1633, made to say he was wrong about what his telescope showed: Jupiter’s moons didn’t circle Earth, and neither did the Sun. Church leaders fumed at Darwin’s ideas, gripping a young Earth like it was their last coin, while Pasteur’s germs knocked their “bad air” nonsense flat. This wasn’t just about different thoughts, it was a big shake-up, pitting a giant system, full of its own importance, against lone brains with tools and grit. Science didn’t charm its way in; it proved its point, stacking evidence until the old walls broke and fell.

Why It Matters in 2025

In 2025, science as a force for progress has the potential to shine brighter than a power plant’s glow, and we need it more than ever. We’re at a turning point, holding technology our great-grandparents couldn’t imagine: machines buzzing toward endless energy, gene editing healing what prayers missed, and satellites watching a heating planet’s heartbeat. Climate change may be the biggest challenge of the 21st century with seas climbing higher, storms hitting harder, but science doesn’t back off, it measures, plans, builds walls and traps carbon. This isn’t just hope; it’s what we got from years of trading belief for facts, begging for knowing. Energy tests in 2025, chasing clean power, build on Michael Faraday’s spinning magnets. Shots hunting cancer lean on Jenner and Pasteur. Floating farms near Jakarta beat hunger with know-how, not wishes. We’re not unbeatable, climate’s tricky, tech can flop, but we’ve got a grip, not just guesses, because science, not Jesus, gave us the wheel.

How did this change happen, one hard step at a time? It kicked off with folks who looked past the sky to what was right there, Copernicus with his star tools, Harvey with his bloody hands, Darwin with his scribbles. Each took on a system that loved being sure more than being curious, a Church that thought truth was its toy, not everyone’s right. They didn’t just tweak ideas; they moved power, from church steps to workbenches, from God’s say-so to human brains guided by facts. Why does it count now, in a year of danger and chance? Because 2025 isn’t paradise, it’s a test. Energy could save us or stall; gene work could cure or mess up; climate fixes could win or wait. Science isn’t a hero, it’s a tool, shaped by those who picked proof over orders, and it’s our best map through the mud.

This series follows that road, from superstition’s hold to evidence’s edge. It begins with Copernicus, kicking the cosmos off its holy spot, and rolls through Harvey, Galileo, Newton, and more, each a piece in a fight against the dark. In 2025, as we tackle a world’s worth of trouble, their story isn’t old news, it’s a guide. Science doesn’t dodge tough stuff; it cuts it open, builds on it. Superstition kept us calm once, but it’s facts that kept us going, lifting us from praying to figuring things out. That’s what’s coming: not perfect, not easy, but real and still growing.

Continue reading Part 2 of Science as a Force for Progress.